Bureaucracies and bureaucrats are resented and despised in many parts of the world and yet they are revered and admired in several states and societies. What accounts for this conundrum?

One set of scholars tends to present bureaucracies as lethargic, corrupt, inefficient, red tape ridden, arrogant, authoritarian and self-serving (David Osborne and Ted Gaebler). The other treats bureaucracy as the State itself – efficient, competitive, merit-driven, laden with technical skills/expertise and institution builders (Douglas North, Acemoglu & Robinson) Perhaps both perspectives are partly correct but it is important to know, how bureaucracies, function and why some excel in governance and bring wealth, economic development and political stability to states and societies?

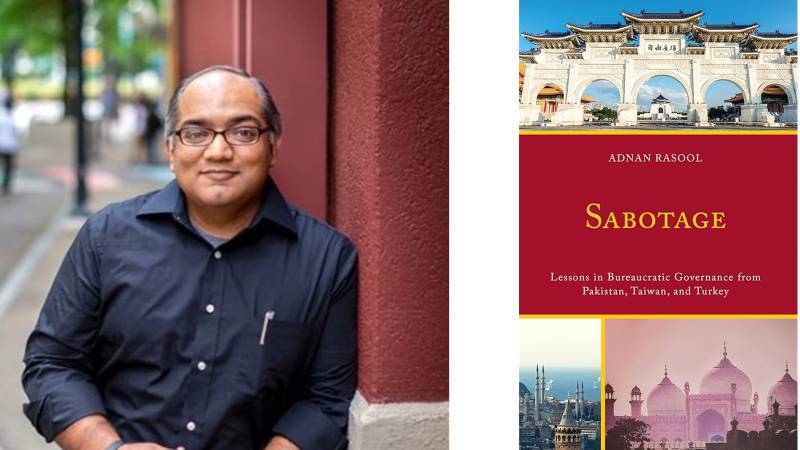

Sabotage: Lessons in Bureaucratic Governance from Pakistan, Taiwan, and Turkey by Adnan Rasool, shows a promising path. It is imaginative, and refreshing in its approach, content and style. It makes you wonder as to who it is that sabotages. Adnan starts by raising a simple – but in Pakistan’s case, opportune and perturbing question – and that is: how do countries keep functioning while undergoing political turmoil? The quest for an answer resulted in this perceptive and delightfully readable book.

The answer that he provides would rankle with many experts and opinion columnists but his response is backed by theoretical rigour, substantial evidence and marshalled with consistency of argument. He argues, “A high quality bureaucracy is meritorious in its structure, has the technical skills to perform the clearly defined functions of the institution and can successfully undertake the policy design as well as implementation.” While the low-quality bureaucracy, “lacks professionalism,” does not have “technical specialisation” or a “meritorious structure of recruitment and promotions.” (p8) He is vigorous in defending the high-quality bureaucracy as key to deflect political chaos and political instability.

While analysing the dynamics of elite competition, contestation and manipulation, he draws an analytical distinction between ruling a country and governing a country. Adnan postulates that institutions ‘govern’ the country, while elites compete, contest and confront to ‘rule’ the country. He contends governance is a “function of how robust are the institutions” and in that continuum, he puts the onus on bureaucracy—policy generation, implementation and provision of services is a function of bureaucracy. It is inclusive of senior civil servants, secretaries, heads of departments and CEOs heading government entities. This leads him to avow that senior bureaucracy enjoys autonomy and can act rationally, particularly in situations where political influence on policy ranges from limited to none. In situations of political chaos, high-quality, professionally competent bureaucracy stays steadfast in weathering the political chaos. Continuing, Adnan explicates governance of the state as “including provision of services, policy generation, and policy implementation, are functions largely dependent on bureaucracy.” He correctly observes that bureaucrats are the only ‘constant’ in government, while autocrats and politicians come and go. Bureaucracies are “nearly impossible” to “dispose of or discard,” because they have “knowledge, access to policy channels, expertise, skills in controlling policy information, retaining institutional memory, dealing with foreign payments, investments and public services largely continue to work.” This is the lesson he has drawn by making a comparative study of three countries: Pakistan, Turkey and Taiwan. Let us see how has he gone about drawing this lesson.

The book has four outstanding features; first, it is theoretically rigorous and makes an effective articulation of innovative network analysis by making a critical appraisal of competencies, technical expertise and professionalism of bureaucracies. Second, it is exceptional and ground-breaking in picking three cases: Pakistan, Turkey and Taiwan.

These countries are culturally and geographically distinct and yet the political systems have similarities: despite episodes of political chaos, the yearning for democracy and democratic movements continue to reappear. By following this theme, the book comes across uniquely different; through each country’s case study, the author illustrates that under conditions of political turmoil, how high-quality bureaucracies are able to provide stability, construct order and deliver services to the citizens. Third, it transmits a comparative analytical method—professionalism of bureaucracies, juxtaposing it to the absence of professionalism among politicians and political parties; fourth, for data collection, interviews and deeper appreciation of ground realities, the author has conducted field research and interviews in Pakistan, Turkey and Taiwan. The book is concise (150 pages) and thematically organised. Each chapter revolves around the central argument for each country, how ‘high quality bureaucracy’ is able to steer its way through under political chaos. The book is divided into six chapters. Chapter 1 is an introduction and lays out the theory and key argument. Chapter 2 hovers around methodology and provides useful information on how he went about collecting data, documents and conducting archival research. I found his fieldwork experience and set of interviews during 2016-17 illuminating. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 are case studies of Pakistan, Taiwan (which, incidentally, Pakistan does not officially recognise as a country) and Turkey. Chapter 6 offers a summation and concluding thoughts on governance stability, his basic theoretical premise.

The case studies of all three countries are meticulous in tracing the similarities of foundational histories. Turkey is seen as emerging from the ashes of the Ottoman empire, ruled by modernist, secular and reformist Kamal Ataturk (1923-1950), a single party rule. The military was the guardian of the state. Taiwan appears as a breakaway province of China, rebelling against the Communist Party and Mao’s leadership, ruled by Kuomintang (KMT), 1949- 88. In the case of Pakistan, he falls back on the legal framework and structure of administration inherited from the British colonial rule as the foundational experience. Initial collapse of party system and ascendency of the military (1958-69 and subsequent military regimes), while bureaucracy endures. For all three cases, he chooses the years 2014 to 2017 and identifies the critical junctures and untangles these skilfully to show how high-quality bureaucracy is able to keep government functioning despite political chaos.

In the case of Turkey, Adnan weaves events to build a persuasive narrative on how from military rule Turkey turns to democratisation, and having reached the pinnacle starts “dismantling a hard-won democracy to a one-party rule.” The Justice and Development Party (AKP) won multiple times but from 2002 onwards and specifically from 2007, the paranoia set in, and it realised its agenda could not be implemented “without total control.” In July 2016, despite the attempted failed coup and political chaos that followed, because of high-quality bureaucracy, the public services in the country continued to function. However, “the mirage of good governance and democracy ended suddenly.” Turkey embarked on a path to autocracy, curbing democracy. Therefore, according to the author, the high-quality bureaucracy was eroded. Turkey’s future as a democracy is uncertain. Hence the chapter is provocatively titled; Institutions Wrecked and Democracy Lost: The Case of Turkey’s Breakdown.

The chapter on Pakistan is aptly titled; Chaotic Stability: The Case of Pakistan’s Governance amid Political Chaos. On Pakistan, he starts with the PTI’s dharnas (massive sit in protests) of 2015-16 and raises this critical question that despite the March/April 2022 protests, how did everything keep functioning while political chaos reigned in the country? Adnan perceptively and persuasively contends, “the bureaucratic governance stability kicks in during political crises, because the bureaucracy is of high quality and enjoys relative autonomy. So even when a severe economic and political crisis is happening, like throughout 2020 and early 2023, the country still functions, meaning that public-service delivery never stops” (pp32-33). He does not shy away from show casing the resilience of Pakistani bureaucracy, fully recognising its multiple disabilities and I endorse that. Institutions govern and sustain chaotic governance stability, while elites contest, antagonise, compete and manipulate to rule.

The chapter titled, Autocratic Roots of Democracy: The Case of Taiwan’s Reformed Bureaucracy is illuminating and insightful. Taiwan underwent transformation from single party rule the KMT to Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). What is significant that President LEE was elected in 1996 and he completed his term in 2000 and that led to KMT-DPP coalition which lasted till 2016. KMT, DPP and Taiwanese bureaucracy emerged as the key players. DPP grows out of KMT and power oscillates between KMT and DPP until 2016. The Taiwanese case shows that bureaucracy “values autonomy and wishes to stay out of politics” (p 93). The case study of Taiwan is tantalising, it offers a framework for how bureaucracy can be “professionalised, sensitised and reformed” and could facilitate democratisation and democratic consolidation(p128). Equally important, it also demonstrates how in a one-party state, the party reforms itself, thus in a way, two-fold professionalisation occurs. For this reason alone, Sabotage: Lessons in Bureaucratic Governance from Pakistan, Taiwan, and Turkey is an opportune venture. The author provides an insightful peep into the causes of political chaos and the resilience, professionalism and competencies of the bureaucracy ensuring continuity and stability.

The book is timely, as democracy is under duress globally and particularly in Turkey and Pakistan, while he brings to attention Taiwan (which had elections recently) as a shining example of a different kind among these three cases.

Here are a few take aways from this study.

Bureaucracies are vital and their technical expertise and skill development is imperative for sustainable development. Therefore, countries must invest in improving methods of recruitment through competition and merit, and institute trainings that inculcate values of public service and professionalism; commensurate pay and performance, technical skills development and induce behavioural change. It is hard to develop high-quality bureaucracy and all too easy to wreck it. Painfully, Pakistan continues to persist on a self-destructive path of bureaucracy-bashing, and that needs correction. For its part, the bureaucracy must embark on a path to reform in its own ‘self-interest’ to retain institutional autonomy, improve quality, develop professional skills by creating space for other professional groups for better delivery of services and provide public goods which would enhance ‘bureaucratic will’ and credibility.

Elected governments need to recognise that as they assume power, in order to set an agenda, devise policies and implement these as policy interventions, they have to rely on bureaucracy.

In Pakistan, the bureaucracy can ‘sabotage’ policies because political parties lack professional skills and capacity to understand how government function is run, and how policies are planned and executed. (p115). Therefore, instead of using bureaucrats as instrument of their personal interests, the politicians need to deploy them as agents of policy change and an arm of policy implementation. This can happen if political parties embrace reform that enhances the organisational structures, professional expertise and sharpens policy focus of the political parties and parliamentarians. For democratic consolidation, a high-quality bureaucracy is a pre-condition and public service is a non-negotiable public good.

Governance is a complex and multi-layered concept and entails, planning, designing policies, looking into implementation and much more importantly it has cultural nuances. High quality bureaucracy contributes to institution building and that guarantees governance stability. Party professionalism contributes to democratic consolidation and political parties need to pay attention on the processes of policy making.

This book cuts across themes of global governance, democracy vs autocracy and security studies. Therefore, academia and students are natural recipients. A must-read for policymakers, political party leaders, journalists, electronic media managers and NGOs – in short all those interested in issues of democracy and good governance would find it engaging in all the three countries.